The morning began with throngs of excited children lined up outside the school, peering through the doors in anxious anticipation of the excitement which awaited them. "Is he here yet?" the children kept asking. No, they were not waiting for a visit from Santa or Thomas the Tank Engine; they were waiting for the arrival of Dr. Doug Kennedy and Rebecca Furuta (optician and vision therapist) of Summit Vision Care, who were coming to teach the children about the parts of an eye, lead them through their first dissection, and conduct free vision screenings at the school.

The morning began with throngs of excited children lined up outside the school, peering through the doors in anxious anticipation of the excitement which awaited them. "Is he here yet?" the children kept asking. No, they were not waiting for a visit from Santa or Thomas the Tank Engine; they were waiting for the arrival of Dr. Doug Kennedy and Rebecca Furuta (optician and vision therapist) of Summit Vision Care, who were coming to teach the children about the parts of an eye, lead them through their first dissection, and conduct free vision screenings at the school.For the past few weeks, in anticipation of their visit, the children have been learning some of the basic anatomy of their eyes (sclera, pupil, iris, cornea, retina, and optic nerve) and gaining a rudimentary understanding of how their eyes function.

How many optometrists do you know who would supply an entire class with cows eyes and dissection tools, spend an entire morning leading preschoolers through their first dissection, and volunteer their time to conduct free vision screenings for the entire class? I only know of one.

Dr. Doug Kennedy has been practicing optometry in Boulder County for sixteen years and owns Summit Vision Care in Erie, Colorado. Although Dr. Kennedy sees patients of all ages (everything from general eye care, to co-management of Lasik and PRK, to specialty contact lens fittings for patients with keratoconic, bifocal, and toric/astigmatism contact prescriptions), his passion and enthusiasm for working with children is particularly palpable. Perhaps it is years of experience working with children, or perhaps it is having children of his own (who attended Montessori schools no less!), but even the most shy and reticent children seem instantly comfortable in his presence. As a result, in addition to being patients of his ourselves, we often recommend his services to families in need of eye care or vision therapies.

So, when Dr. Kennedy volunteered to donate a morning of his time to conduct free vision screenings at the school, I was absolutely elated. Few things are as disheartening to a teacher as the idea that there are children desperately interested in learning who are struggling because they cannot see clearly. Nevertheless, according to the National Institutes of Health, more than 1 out of every 20 children in America is currently struggling with an undiagnosed vision problem. These undiagnosed and untreated vision problems are significant contributors to reading problems, developmental delays, poor school performance, poor concentration and emotional regulation, and to special education classifications. In fact, it is estimated by the NIH that 60% of "problem learners" have undiagnosed vision problems contributing to their difficulties. In many cases, serious vision problems can be prevented or reversed with early detection and prevention.

I was particularly excited because, in addition to testing the children for both distance and near visual acuity, Dr. Kennedy was also kind enough to perform retinoscopy (an objective measurement of the refractive condition of the eye which is particularly useful for examining children because it ensures that their judgments and subjective responses match the prescription), test their extra ocular motilities (how their eyes focus, track, and move independently and in concert with each other so that the brain can take input from each eye and form a single image), and screen the children for eye teaming issues (which make it very difficult for children to be able to focus and align their eyes together while viewing objects up close, causing blurred or double vision and responsible for a large percentage of reading problems). These additional tests are generally not included in school vision screenings (most screenings only test the child's distance acuity), but are particularly important because convergence issues are common and often go undiagnosed (proper testing is seldom included in eye tests performed in a pediatrician's office or in school screenings and children can pass a 20/20 eye chart test and still have convergence issues).

And so it began. The children anxiously awaited Dr. Kennedy's arrival, and then enthusiastically peered into the classroom hoping to get a glimpse of the preparations that Dr. Kennedy and Rebecca Furuta, were making. Once the eager children were welcomed into the classroom, they sat down and listened with rapt attention as Dr. Kennedy reviewed the basic structures of the eye using anatomical models.

And so it began. The children anxiously awaited Dr. Kennedy's arrival, and then enthusiastically peered into the classroom hoping to get a glimpse of the preparations that Dr. Kennedy and Rebecca Furuta, were making. Once the eager children were welcomed into the classroom, they sat down and listened with rapt attention as Dr. Kennedy reviewed the basic structures of the eye using anatomical models.

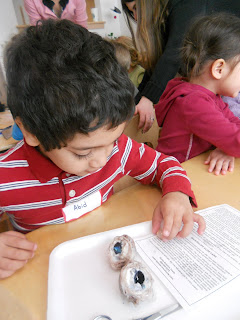

Then, it was time to proceed with the dissection! Like any good father, Dr. Kennedy had spent some quality time with his own children over the past few days, engaging them in trimming the extra fat off of the cow's eyes to prepare them for dissection. If he had any reservations about handing dissection tools over to our pint sized scientists and turning them lose to dissect, he was the consummate Montessori parent and didn't let it show.

Then, it was time to proceed with the dissection! Like any good father, Dr. Kennedy had spent some quality time with his own children over the past few days, engaging them in trimming the extra fat off of the cow's eyes to prepare them for dissection. If he had any reservations about handing dissection tools over to our pint sized scientists and turning them lose to dissect, he was the consummate Montessori parent and didn't let it show.Dissecting cow's eyes is a classic kindergarten anatomy lesson. It is the perfect dissection experience for children this age because the structures are relatively large, the cuts are simple and minimal, and the interior of the eye is so interesting (interesting textures, beautiful colors, and such an interesting function). Nevertheless, I was a little uncertain of what to expect as far as the reaction of the students when the eyes were actually placed in front of them. Would they want to touch them? I need not have worried. It is always really wonderful when you encounter someone with a real passion and zeal for what they do, and it really is contagious. That is how I would describe dissecting cow's eyes with Dr. Kennedy. His interest in the subject was infectious; any children (or adults, for that matter) that were hesitant about dissecting were immediately enthralled and engaged.

He talked the children through the dissection, beginning with an observation of the external anatomy of the eyes. The children easily identified the sclera (the white, outer, protective layer of the eye), the cornea (the transparent front part of the eye that covers the iris and the pupil), and the optic nerve. The eyes were really great specimens (one had a very pronounced optic nerve still attached) and the children were completely captivated.

He talked the children through the dissection, beginning with an observation of the external anatomy of the eyes. The children easily identified the sclera (the white, outer, protective layer of the eye), the cornea (the transparent front part of the eye that covers the iris and the pupil), and the optic nerve. The eyes were really great specimens (one had a very pronounced optic nerve still attached) and the children were completely captivated.

Then, Dr. Kennedy taught the children about the internal anatomy of the eye. They cut the eyes in half and (much to their delight) saw that the inside of the eye cavity was filled with a gelatinous liquid called the vitreous.

Then, Dr. Kennedy taught the children about the internal anatomy of the eye. They cut the eyes in half and (much to their delight) saw that the inside of the eye cavity was filled with a gelatinous liquid called the vitreous.

The children were quite interested in this unexpected finding. They spent quite a bit of time investigating the vitreous and many students stated later that this was their favorite part of the dissection (when one parent picked up, her three year old daughter was literally jumping up and down while she told her mom that her eye was filled with "vitreous jelly"). We also had an amusing moment in which one girl became dismayed to find that she had tipped over one of the halves of her eye and spilled vitreous fluid and Dr. Kennedy joked with her that no one should "cry over spilled vitreous fluid" (optometrist humor!).

The children were quite interested in this unexpected finding. They spent quite a bit of time investigating the vitreous and many students stated later that this was their favorite part of the dissection (when one parent picked up, her three year old daughter was literally jumping up and down while she told her mom that her eye was filled with "vitreous jelly"). We also had an amusing moment in which one girl became dismayed to find that she had tipped over one of the halves of her eye and spilled vitreous fluid and Dr. Kennedy joked with her that no one should "cry over spilled vitreous fluid" (optometrist humor!).

Equally exciting, was the discovery that behind the "vitreous jelly" lay a small, clear lens. Dr. Kennedy encouraged them to pull the lens out of the eyes, and I was somewhat surprised to find that even children who had seemed slightly reluctant at the beginning were now confidently sticking their fingers into the vitreous to pull out the lens.

Equally exciting, was the discovery that behind the "vitreous jelly" lay a small, clear lens. Dr. Kennedy encouraged them to pull the lens out of the eyes, and I was somewhat surprised to find that even children who had seemed slightly reluctant at the beginning were now confidently sticking their fingers into the vitreous to pull out the lens.

I admit that although I have fond memories of doing dissections in science classes as a child (I always found them interesting), I had forgotten just how intriguing they can be. After removing the lenses, the children (and the adults) placed them over paper with writing on it and saw that it magnified the objects. Both the adults and the children found this to be really exciting!

I admit that although I have fond memories of doing dissections in science classes as a child (I always found them interesting), I had forgotten just how intriguing they can be. After removing the lenses, the children (and the adults) placed them over paper with writing on it and saw that it magnified the objects. Both the adults and the children found this to be really exciting!

After that, the children located the retina (the part of the eye that contains the photoreceptor cells that collect the light which enters the eye from the outside world), the black choroid coat (which supplies the eye with blood and nutrients), and the beautiful iridescent tapetum lucidum (a reflective material found in cow's eyes, but not in human eyes, which allows them to see better at night by reflecting the light which is absorbed through the retina back into the retina).

After that, the children located the retina (the part of the eye that contains the photoreceptor cells that collect the light which enters the eye from the outside world), the black choroid coat (which supplies the eye with blood and nutrients), and the beautiful iridescent tapetum lucidum (a reflective material found in cow's eyes, but not in human eyes, which allows them to see better at night by reflecting the light which is absorbed through the retina back into the retina). Then, the children peeled back the cornea to locate the iris (the colored part of the eye which controls the diameter and size of the pupil, and how much light reaches the retina).

Then, the children peeled back the cornea to locate the iris (the colored part of the eye which controls the diameter and size of the pupil, and how much light reaches the retina). Having dissected and viewed the basic structures of the eye, it was time to clean up; however, much to our amusement, the children protested. They wanted to take the eyes home with them! After much negotiating, hands were washed, tables were cleaned and disinfected, eye balls were disposed of, and the happy children were taken for individual vision screenings.

Having dissected and viewed the basic structures of the eye, it was time to clean up; however, much to our amusement, the children protested. They wanted to take the eyes home with them! After much negotiating, hands were washed, tables were cleaned and disinfected, eye balls were disposed of, and the happy children were taken for individual vision screenings.

After vision screenings were complete, and Dr. Kennedy and Rebecca had taken the time to write thorough reports for each child, the children went outside to play while Dr. Kennedy packed up and we set up for lunch. When he was ready to leave, he walked outside and was inundated with children. Spontaneously, they began hugging him and thanking him for coming to speak with them. I honestly doubt that there is an optometrist anywhere who is more beloved.

In the afternoon, many of the children decided to make him thank you cards, while others asked me if he would come back again. I have to say, we are fortunate in that we get to do a lot of fun and interesting things together as a class, but I cannot think of many that I have found as interesting and enjoyable.

We would sincerely like to thank Dr. Kennedy and Rebecca Furuta for sharing their time and expertise with us, and for the donation of the dissection materials. In addition to ensuring that there is not a child in our classroom suffering from an undiagnosed visual impairment, they also made sure that every child left with a really positive experience (I can guarantee that no child in this class will ever be afraid of going to see an optometrist for an eye examination). There certainly could be one or two future optometrists in the class!

For more information about Dr. Kennedy and his practice, please visit the Summit Vision Care website at:

The American Optometric Association (AOA) recommends that all children receive a comprehensive eye exam at six months of age (the AOA launched a national program called InfantSEE in which participating providers, like Dr. Kennedy, will provide a free examination to children between six months and one year of age- visit http://www.infantsee.org/ to learn more or to find a participating provider), every year after, and any time the child exhibits signs of a vision problem (burning, itching, or watery eyes, holding books too close to their eyes while reading, bumping into things, excessive daydreaming, difficulty with fine motor tasks, closing eyes or tilting their head, eyes that do not appear to focus correctly, short attention spans during reading or homework, or difficulty or dislike of reading, writing, or copying). In addition to checking your child's eye sight, a comprehensive examination can diagnose conditions like "lazy eye," "crossed eye," and ocular diseases. Early detection and intervention can be critical to successful treatment and to preventing developmental delays. An annual examination by an optometrist is more comprehensive than the vision screenings children receive at school and in their pediatrician's office; while these screenings can detect visual acuity issues, they should not serve in lieu of an annual exam by an optometrist.

Thank you Dr. Kennedy!

No comments:

Post a Comment